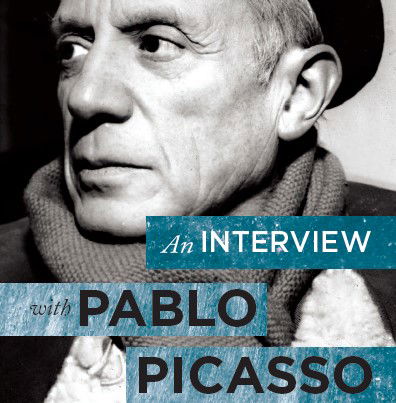

Artists, Picasso said, “should invent, not just copynature like an ape.

Artists, Picasso said, “should invent, not just copynature like an ape.” If a two-dimensional duplicate of the world is wanted, the modernist argument ran,then photography is always going to supply that much moreefficiently than painting.Since the 1860s, self-consciously modern art had defineditself as post-photographic, always seeking a different reasonto be looked at, something other than a surface impressionof the world. Before cubism, modern painting had flirtedwith this break-up of coherence.

by Simon Schama

image credit: Simon Schama

Van Gogh, for instance,chose the color of things and people according to emotiveperception rather than optically observed hue. However,around 1910, Picasso and his friend, Georges Braque, werestirred by Paul Cézanne’s late destructions of solid form intocrystallographically faceted structures that were somehowboth broken and coherent at the same time—and theyconsequently went for the kill. Bye-bye, resemblance.The departure from resemblance pointed in twodirections: decoration or sculpture. The decorative way—chosen, for example, by Matisse—was the road to abstraction:shimmering arrangements of flat, brilliant color designedto set our senses dancing and put a smile on our faces.Picasso, the least sentimental and the most sculptural of allmodern artists, went the other way, wanting somehow to register the tactile in paint. Although he spoke of his cubistexperiments as beginning in pure compositional painting,he also insisted that they were paintings of something otherthan themselves. Deep within the slinky-toy cubist unfurlingsof form, seen as if juddering through time, was somethingsubstantial and concrete. The simultaneous multi-dimensionalrendering of different aspects of a figure was, somehow, arepresentation of what that figure truly was. No colors otherthan those of engineering and architecture—rusty browns,dusty ochres, and steel greys—were to distract the viewerfrom the exposed scaffolding on which he hung that idea offundamental form.The provocation was entered into in the utmost goodfaith. By blowing up the apparent look of things—andpeople—the cubists were saying that they were offeringan alternative reality, the reality of memory or shiftingperception. “Any form that conveys to us the sense of reality,”Picasso said many years later, “is the one furthest removedfrom the reality of the retina; the eyes of the artist are opento a superior reality; his works are evocations.”